Difference in differences

Difference in differences (DID) (sometimes 'Diff-in-Diffs') is a quasi-experimental technique used in econometrics that measures the effect of a treatment at a given period in time. It is often used to measure the change induced by a particular treatment or event, though may be subject to certain biases (mean reversion bias, etc.). In contrast to a within-subjects estimate of the treatment effect (that measures the difference in an outcome after and before treatment) or a between-subjects estimate of the treatment effect (that measures the difference in an outcome between the treatment and control groups), the DID estimator represents the difference between the pre-post, within-subjects differences of the treatment and control groups.

The basic premise of DID is to examine the effect of some sort of treatment by comparing the treatment group after treatment both to the treatment group before treatment and to some other control group. Naively, you might consider simply looking at the treatment group before and after treatment to try to deduce the effect of the treatment. However, a lot of other things were surely going on at exactly the same time as the treatment. DID uses a control group to subtract out other changes at the same time, assuming that these other changers were identical between the treatment and control groups. (The Achilles' heel of DID is when something else changes between the two groups at the same time as the treatment.) For it to be an accurate estimation, we must also assume that the composition of the two groups remains the same over the course of the treatment. Also we need to consider the possible serial correlation issues.

Contents |

Hypothetical example

Consider this example:[1] state A passes a bill offering tax deduction to employers providing health insurance. Let us also consider that in the year after the bill passed (year 2) the percentage of firms offering health insurance increased by 30% compared to the year before the bill was passed (year 1). To estimate the impact of the bill on the percentage of firms offering health insurance, we could simply do a before and after analysis and conclude that the bill increased insurance offerings by 30%. The problem is that there could be a trend over time for more employers to offer insurance. It is impossible to identify if the tax deductibility or the time trend caused this increase in firm offering.

One way to identify the impact of the bill is to run a DID regression. If there is a state B that did not change the way it treated employer provided health insurance, we could use this as a control group to compare the changes between A and B between the two years.

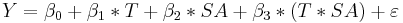

We will run the regression:

where Y is the percentage of firms offering health insurance in each state in each time period. T is a time dummy, SA is a state dummy for state A, and T*SA is the interaction of the time dummy and the state A dummy.

The chart below displays the percentage of firms offering insurance in each state and time period.

| State A | State B | |

|---|---|---|

| Year 1 | b | a |

| Year 2 | d | c |

The next chart explains what each coefficient in the regression represents.

| Coefficient | Calculation |

|---|---|

|

a |

|

c − a |

|

b − a |

|

(d − b) − (c − a) |

We can see that  is the baseline average,

is the baseline average,  represents the time trend in the control group,

represents the time trend in the control group,  represents the differences between the two states in year 1, and

represents the differences between the two states in year 1, and  represents the difference in the changes over time. Assuming that both states have the same health insurance trends over time, we have now controlled for a possible national time trend. We can now identify what the true impact of the tax deductibility is on employers offering insurance.

represents the difference in the changes over time. Assuming that both states have the same health insurance trends over time, we have now controlled for a possible national time trend. We can now identify what the true impact of the tax deductibility is on employers offering insurance.

Real example

Consider one of the more famous DID studies, Card and Krueger article on minimum wage in New Jersey, published in September 1994.[2]

Card and Krueger are looking at the effect of an April 1, 1992 increase in NJ's minimum wage from $4.25 to $5.05. They collect data on fast food employment before (February) and after (November) the change. In NJ, average employment per restaurant rises from 20.44 FTEs before the wage change to 21.03 FTE's after the wage change. Naively, you might interpret this to mean that the minimum wage change caused a 0.59 FTE increase in employment per store. But lots of other things changed. For one thing, we're in a different season; do fast food restaurants face more demand in winter than in spring? For another thing, the macroeconomic conditions may have changed more broadly. Perhaps unemployment is shrinking across the board. Perhaps employment would have gone up by even more in the absence of the minimum wage increase.

Card and Krueger needed a control group. They turn to fast food restaurants in Pennsylvania, a state that faces very similar macroeconomic conditions. They expect that major changes in the fast food environment in NJ are probably also occurring in PA. In PA, FTE employment actually fell from April to November, from 23.33 to 21.17.

If you think fast food restaurants in PA are identical to fast food restaurants in NJ, then you expect NJ restaurants to see a similar −2.16 FTE change in employment. Instead, we see a +0.59 change. So employment in NJ rose by 2.76 FTEs more than we would expect just based on what was happening in PA.

That is, we take the difference between Period 1 and Period 2 separately for the treatment and control groups (+0.59 and −2.16). Then we calculate the difference between those two differences (0.59 − (−2.16)) to get the DID estimate.

We know one major difference between NJ and PA at the time: the change in the minimum wage. The DID method thus implies that the minimum wage increase appears to have led to a 2.76 increase in FTEs per fast food restaurant. (This is probably not going to convince you that raising the minimum wage raises employment, but at the very least it strongly implies that a minimum wage hike cannot DECREASE fast-food employment by all that much.)

The Card and Krueger paper goes into quite a bit more detail, of course, including several other specifications of the same basic concept; reading it is a good tutorial on the method.

Critics

Bertrand et al. in an article published in the Quarterly Journal of Economics in February 2004 asked the question How Much Should We Trust Differences-in-Differences Estimates? and apparently the answer is "not all that much." According to Bertrand et al. most papers that employ Difference-in-Differences estimation use many years of data and focus on serially correlated outcomes but ignore that the resulting standard errors are inconsistent, leading to serious over-estimation of t-statistics and significance levels.[3] These conventional DID standard errors severely understate the standard deviation of the estimators: we find an "effect" significant at the 5 percent level for up to 45 percent of the placebo interventions. To alleviate this problem two corrections based on asymptotic approximation of the variance-covariance matrix work well for moderate numbers of states and one correction that collapses the time series information into a "pre" and "post" period and explicitly takes into account the effective sample size works well even for small numbers of states.

See also

References

- ^ Difference in Difference Estimation

- ^ David Card and Alan B. Krueger, "Minimum Wages and Employment: A Case Study of the Fast-Food Industry in New Jersey and Pennsylvania," American Economic Review, v. 84, n. 4 (September 1994), pp. 774–775.

- ^ Bertrand, M.; Duflo, E.; Mullainathan, S. "How Much Should We Trust Differences-in-Differences Estimates?" The Quarterly Journal of Economics, v. 119, n. 1, p. 249-275, February 2004.

External links

- How Does Charitable Giving Respond to Incentives and Income? Dynamic Panel Estimates Accounting for Predictable Changes in Taxation, National Bureau of Economic Research, July 2005

- T. Conley and C. Taber, "Inference with "Difference in Differences" with a Small Number of Policy Changes", National Bureau of Economic Research, July 2005